Apuleius’s fairy tale of the victory of innocence over jealousy and desire.

Apuleius (124-170AD) is the author of the only Latin novel to survive in it’s entirety : The Golden Ass. Nestled inside it is the story of Psyche and Cupid. Apuleius himself calls it a Fairy Tale. What first drew me to the story was that the heroine’s name, Psyche, is from the Greek for “soul” or spirit”. So the title can be read: “The Soul and the God of Desire”. In this story, the Soul (Psyche) defeats the jealousy of the goddess of Beauty, and tames the god of Desire with marriage. Images often emphasize the erotic aspects of the story, which I think misses Apuleius’s intention entirely.

I found myself in good company in this interpretation when I discovered C.S.Lewis’s “Till We Have Faces”. This is a re-telling of the story from the view point of Psyche’s sister, and though he gives the tale a strong Catholic feeling, a quote from the novel seems to be very germane to the discussion on this site concerning the difference between Naturalism and Symbolist intentions.

“And for all I can tell, the only difference (between reality and dream) is that what many see we call a real thing, and what only one sees we call a dream. But things that many see may have no taste or moment in them at all, and things that are shown only to one may be spears and water-spouts of truth from the very depth of truth.”

Mr. Lewis would not mind, I hope, if I add that Naturalists and scientists find great moment and have a great taste for “things that many see”. And a Symbolist, while he may share their interest, is looking to the “things that are shown only to one” for “spears and water-spouts of truth from the very depth of truth.”

What also captured my imagination was that its form is the form of the much older masculine Hero Myths: Theseus, Heracles, Jason. Psyche is a heroine who accomplishes several difficult tasks and rises victorious. It is hard for me to think Apuleius was not trying to give to women their own Hero Myth.

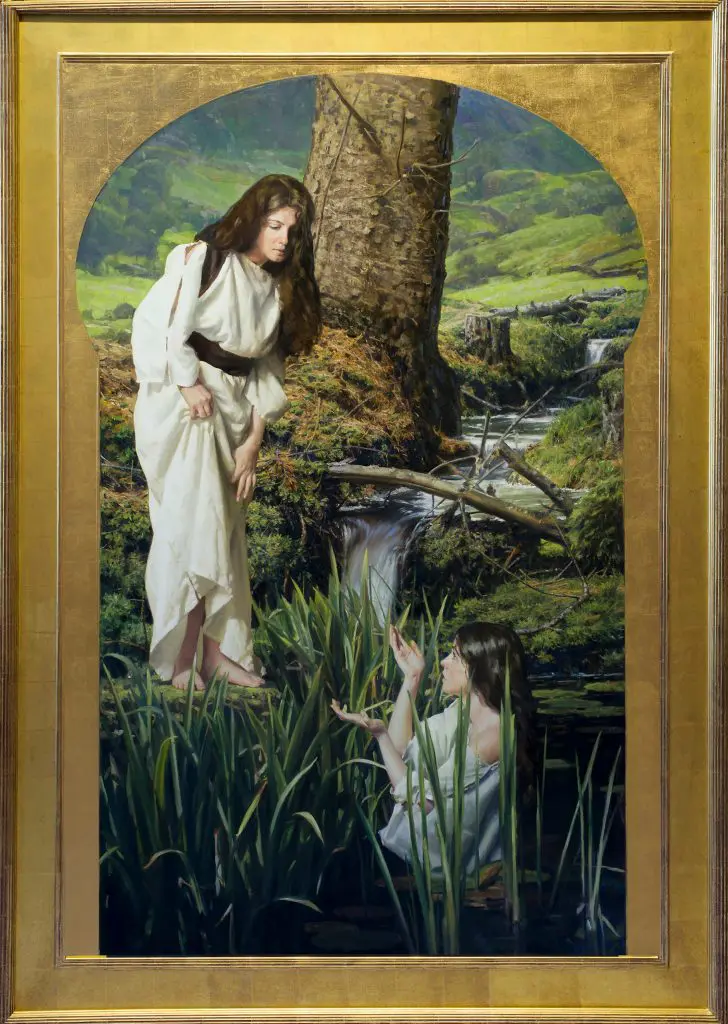

What follows here is the original text of Apuleius in its entirety with my paintings set in place at the appropriate spots. As more pieces are completed they will be added.

Apuleius: Cupid and Psyche from “The Golden Ass” (ca. 150 A.D.)

There was once a city with a king and queen who had three beautiful daughters. The two eldest were very fair to see, but not so beautiful that human praise could not do them justice. The loveliness of the youngest, however, was so perfect that human speech was too poor to describe or even praise it satisfactorily. Indeed huge numbers of both citizens and foreigners, drawn together in eager crowds by the fame of such an extraordinary sight, were struck dumb with admiration of her unequalled beauty; and putting right thumb and forefinger to their lips they would offer outright religious worship to her as the goddess Venus. Meanwhile the news had spread through the nearby cities and adjoining regions that the goddess born of the blue depths of the sea and fostered by its foaming waves had made public the grace of her godhead by mingling with mortal men; or at least that, from a new fertilization by drops from heaven, not sea but earth had grown another Venus in the flower of her virginity.

And so this belief exceeded all bounds and gained ground day by day,ranging first through the neighbouring islands, then, as the report made its way further afield, through much of the mainland and most of the provinces. Now crowds of people came flocking by long journeys and deep-sea voyages to view this wonder of the age. No one visited Paphos or Cnidos or even Cythera to see the goddess herself; her rites were abandoned, her temples disfigured, her couches trampled, her worship neglected; her statues were ungarlanded, her altars shamefully cold and empty of offerings. It was the girl to whom prayers were addressed, and in human shape that the power of the mighty goddess was placated. When she appeared each morning it was the name of Venus, who was far away, that was propitiated with sacrifices and offerings; and as she walked the streets the people crowded to adore her with garlands and flowers.

This outrageous transference of divine honours to the worship of a mortal girl kindled violent anger in the true Venus, and unable to contain her indignation, tossing her head and protesting in deep bitterness, she thus soliloquized: ‘So much for me, the ancient mother of nature, primeval origin of the elements, Venus nurturer of the whole world: I must go halves with a mortal girl in the honour due to my godhead, and my name, established in heaven, is profaned by earthly dirt! It seems that I am to be worshipped in common and that I must put up with the obscurity of being adored by deputy, publicly represented by a girl – a being who is doomed to die! Much good it did me that the shepherd whose impartial fairness was approved by great Jove preferred me for my unrivalled beauty to those great goddesses! But she will rue the day, whoever she is, when she usurped my honours. I’ll see to it that she regrets this beauty of hers to which she has no right.’

So saying, she summoned that winged son of hers, that most reckless of creatures, whose wicked behaviour flies in the face of public morals, who armed with torch and arrows roams at night through houses where he has no business, ruining marriages on every hand, committing heinous crimes with impunity, and never doing such a thing as a good deed. Irresponsible as he already was by nature, she aroused him yet more by her words; and taking him to the city and showing him Psyche – this was the girl’s name – she laid before him the whole story of this rival beauty. Groaning and crying out in indignation, ‘By the bonds of a mother’s love,’ she said, ‘I implore you, by the sweet wounds of your arrows, by the honeyed burns made by your torch, avenge your mother – avenge her to the full. Punish mercilessly that arrogant beauty, and do this one thing willingly for me – it’s all I ask. Let this girl be seized with a burning passion for the lowest of mankind, some creature cursed by Fortune in rank, in estate, in condition, someone so degraded that in all the world he can find no wretchedness to equal his own.’

With these words, she kissed her son with long kisses, open- mouthed and closely pressed, and then returned to the nearest point of the seashore. And as she set her rosy feet on the surface of the moving waves, all at once the face of the deep sea became bright and calm. Scarcely had she formed the wish when immediately, as if she had previously ordered it, her marine entourage was prompt to appear. There came the daughters of Nereus singing in harmony, Portunus with his thick sea-green beard, Salacia, the folds of her robe heavy with fish, and little Palaemon astride his dolphin. On all sides squadrons of Tritons cavorted over the sea. One softly sounded his loud horn, a second with a silken veil kept off the heat of her enemy the Sun, a third held his mistress’s mirror before her face, and others yoked in pairs swam beneath her car. Such was the retinue that escorted Venus in her progress to Ocean.

Psyche meanwhile, for all her striking beauty, had no joy of it.

Everyone feasted their eyes on her, everyone praised her, but no one, king, prince, or even commoner, came as a suitor to ask her in marriage. Though all admired her divine loveliness, they did so merely as one admires a statue finished to perfection. Long ago her two elder sisters, whose unremarkable looks had enjoyed no such widespread fame, had been betrothed to royal suitors and achieved rich marriages; Psyche stayed at home an unmarried virgin mourning her abandoned and lonely state, sick in body and mind, hating this beauty of hers which had enchanted the whole world.

In the end the unhappy girl’s father, sorrowfully suspecting that the gods were offended and fearing their anger, consulted the most ancient oracle of Apollo at Miletus, and implored the great god with prayers and sacrifices to grant marriage and a husband to his slighted daughter. But Apollo, though Greek and Ionian, in consideration for the writer of a Milesian tale, replied in Latin:

On mountain peak, O King, expose the maid

For funeral wedlock ritually arrayed.

No human son-in-law (hope not) is thine,

But something cruel and fierce and serpentine;

That plagues the world as, borne aloft on wings,

With fire and steel it persecutes all things;

That Jove himself, he whom the gods revere,

That Styx’s darkling stream regards with fear.

The king had once accounted himself happy; now, on hearing the utterance of the sacred prophecy, he returned home reluctant and downcast, to explain this inauspicious reply, and what they had to do, to his wife. There followed several days of mourning, of weeping, of lamentation. Eventually the ghastly fulfilment of the terrible oracle was upon them. The gear for the poor girl’s funereal bridal was prepared; the flame of the torches died down in black smoke and ash; the sound of the marriage-pipe was changed to the plaintive Lydian mode; the joyful marriage-hymn ended in lugubrious wailings; and the bride wiped away her tears with her own bridal veil. The whole city joined in lamenting the sad plight of the afflicted family, and in sympathy with the general grief all public business was immediately suspended.

However, the bidding of heaven had to be obeyed, and the unfortunate Psyche was required to undergo the punishment ordained for her. Accordingly, amid the utmost sorrow, the ceremonies of her funereal marriage were duly performed, and escorted by the entire populace Psyche was led forth, a living corpse, and in tears joined in, not her wedding procession, but her own funeral. While her parents, grief-stricken and stunned by this great calamity, hesitated to complete the dreadful deed, their daughter herself encouraged them: ‘Why do you torture your unhappy old age with prolonged weeping? Why do you weary your spirit – my spirit rather – with constant cries of woe? Why do you disfigure with useless tears the faces which I revere? Why by tearing your eyes do you tear mine? Why do you pull out your white hairs? Why do you beat your breasts, those breasts which to me are holy? These, it seems, are the glorious rewards for you of my incomparable beauty. Only now is it given to you to understand that it is wicked Envy that has dealt you this deadly blow. Then, when nations and peoples were paying us divine honours, when with one voice they were hailing me as a new Venus, that was when you should have grieved, when you should have wept, when you should have mourned me as already lost. Now I too understand, now I see that it is by the name of Venus alone that I am destroyed. Take me and leave me on the rock to which destiny has assigned me. I cannot wait to enter on this happy marriage, and to see that noble bridegroom of mine. Why should I postpone, why should I shirk my meeting with him who is born for the ruin of the whole world?’

After this speech the girl fell silent, and with firm step she joined the escorting procession. They came to the prescribed crag on the steep mountain, and on the topmost summit they set the girl and there they all abandoned her; leaving there too the wedding torches with which they had lighted their path, extinguished by their tears, with bowed heads they took their way homeward.

Psyche’s unhappy parents, totally prostrated by this great calamity, hid themselves away in the darkness of their shuttered palace and abandoned themselves to perpetual night. Her, however, fearful and trembling and lamenting her fate there on the summit of the rock, the gentle breeze of softly breathing Zephyr, blowing the edges of her dress this way and that and filling its folds, imperceptibly lifted up; and carrying her on his tranquil breath smoothly down the slope of the lofty crag he gently let her sink and laid her to rest on the flowery turf in the bosom of the valley that lay below.

In this soft grassy spot Psyche lay pleasantly reclining on her bed of dewy turf and, her great disquiet of mind soothed, fell sweetly asleep. Presently, refreshed by a good rest, she rose with her mind at ease. What she now saw was a park planted with big tall trees and a spring of crystal-clear water. In the very center of the garden, by the outflow of the spring, a palace had been built, not by human hands but by a divine craftsman. Directly you entered you knew that you were looking at the pleasure-house of some god-so splendid and delightful it was. For the coffering of the ceiling was of citron-wood and ivory artfully carved, and the columns supporting it were of gold; all the walls were covered in embossed silver, with wild beasts and other animals confronting the visitor on entering. Truly, whoever had so skillfully imparted animal life to all that silver was a miracle-worker or a demigod or indeed a god! Furthermore, the very floors were divided up into different kinds of pictures in mosaic of precious stones: twice indeed and more than twice marvelously happy those who walk on gems and jewelry! As far and wide as the house extended, every part of it was likewise of inestimable price. All the walls, which were built of solid blocks of gold, shone with their own brilliance, so that the house furnished its own daylight, sun or no sun; such was the radiance of the rooms, the colonnades, the very doors. The rest of the furnishings matched the magnificence of the building, so that it would seem fair to say that great Jove had built himself a heavenly palace to dwell among mortals.

Drawn on by the delights of this place, Psyche approached and, becoming a little bolder, crossed the threshold; then, allured by her joy in the beautiful spectacle, she examined all the details. On the far side of the palace she discovered lofty storehouses crammed with rich treasure; there is nothing that was not there. But in addition to the wonder that such wealth could exist, what was most astonishing was that this vast treasure of the entire world was not secured by a single lock, bolt, or guard. As she gazed at all this with much pleasure there came to her a disembodied voice: ‘Mistress, you need not be amazed at this great wealth. All of it is yours. Enter then your bedchamber, sleep off your fatigue, and go to your bath when you are minded. We whose voices you hear are your attendants who will diligently wait on you; and when you have refreshed yourself a royal banquet will not be slow to appear for you.’ Psyche recognized her happy estate as sent by divine Providence, and obeying the instructions of the bodiless voice she dispelled her weariness first with sleep and then with a bath. There immediately appeared before her a semicircular seat; seeing the table laid she understood that this provision was for her entertainment and gladly took her place. Instantly course after course of wine like nectar and of different kinds of food was placed before her, with no servant to be seen but everything wafted as it were on the wind. She could see no one but merely heard the words that were uttered, and her waiting maids were nothing but voices to her. When the rich feast was over, there entered an invisible singer, and another performed on a lyre, itself invisible. This was succeeded by singing in concert, and though not a soul was to be seen, there was evidently a whole choir present. These pleasures ended, at the prompting of dusk Psyche went to bed. Night was well advanced when she heard a gentle sound. Then, all alone as she was and fearing for her virginity, Psyche quailed and trembled, dreading, more than any possible harm, the unknown. Now there entered her unknown husband; he had mounted the bed, made her his wife, and departed in haste before sunrise. At once the voices that were in waiting in the room ministered to the new bride’s slain virginity. Things went on in this way for some little time; and, as is usually the case, the novelty of her situation became pleasurable to her by force of habit, while the sound of the unseen voice solaced her solitude.

Meanwhile her parents were pining away with ceaseless grief and sorrow; and as the news spread her elder sisters learned the whole story. Immediately, sad and downcast, they left home and competed with each other in their haste to see and talk to their parents. That night her husband spoke to Psyche – for though she could not see him, her hands and ears told her that he was there – as follows: ‘Sweetest Psyche, my dear wife, Fortune in yet more cruel guise threatens you with mortal danger: I charge you to be most earnestly on your guard against it. Your sisters, believing you to be dead, are now in their grief following you to the mountain-top and will soon be there. If you should hear their lamentations, do not answer or even look that way, or you will bring about heavy grief for me and for yourself sheer destruction.’ She agreed and promised to do her husband’s bidding, but as soon as he and the night had vanished together, the unhappy girl spent the whole day crying and mourning, constantly repeating that now she was utterly destroyed: locked up in this rich prison and deprived of intercourse or speech with human beings, she could not bring comfort to her sisters in their sorrow or even set eyes on them. Unrevived by bath or food or any other refreshment and weeping inconsolably she retired to rest.

It was no more than a moment before her husband, earlier than usual, came to bed and found her still in tears. Taking her in his arms he remonstrated with her: ‘Is this what you promised, my Psyche? I am your husband: what am I now supposed to expect from you? What am I supposed to hope? All day, all night, even in your husband’s arms, you persist in tormenting yourself. Do then as you wish and obey the ruinous demands of your heart. Only be mindful of my stern warning when – too late – you begin to be sorry.’ Then with entreaties and threats of suicide she forced her husband to agree to her wishes: to see her sisters, to appease their grief, to talk with them.

So he yielded to the prayers of his new bride, and moreover allowed her to present them with whatever she liked in the way of gold or jewels, again and again, however, repeating his terrifying warnings: she must never be induced by the evil advice of her sisters to discover what her husband looked like, or allow impious curiosity to hurl her down to destruction from the heights on which Fortune had placed her, and so for ever deprive her of his embraces. Psyche thanked her husband and, happier now in her mind, ‘Indeed,’ she said, ‘I will die a hundred deaths before I let myself be robbed of this most delightful marriage with you. For I love and adore you to distraction, whoever you are, as I love my own life; Cupid himself cannot compare with you. But this too I beg you to grant me: order your servant Zephyr to bring my sisters to me as he brought me here’ and planting seductive kisses, uttering caressing words, and entwining him in her enclosing arms, she added to her endearments ‘My darling, my husband, sweet soul of your Psyche.’ He unwillingly gave way under the powerful influence of her murmured words of love, and promised to do all she asked; and then, as dawn was now near, he vanished from his wife’s arms.

The sisters inquired the way to the rock where Psyche had been left and hurriedly made off to it, where they started to cry their eyes out and beat their breasts, so that the rocky crags re-echoed their ceaseless wailings. They went on calling their unhappy sister by name, until the piercing noise of their shrieks carried down the mountainside and brought Psyche running out of the palace in distraction, crying; ‘Why are you killing yourselves with miserable lamentation for no reason? I whom you are mourning, I am here. Cease your sad outcry, dry now your cheeks so long wet with tears; for now you can embrace her for whom you were grieving.’ Then she summoned Zephyr and reminded him of her husband’s order. On the instant he obeyed her command and on his most gentle breeze at once brought them to her unharmed. Then they gave themselves over to the enjoyment of embraces and eager kisses; and coaxed by their joy the tears which they had restrained now broke out again. ‘But now,’ said Psyche, ‘enter in happiness my house and home and with your sister restore your tormented souls.’ With these words she showed them the great riches of the golden palace and let them listen to the retinue of slave-voices, and refreshed them sumptuously with a luxurious bath and the supernatural splendours of her table. They, having enjoyed to the full this profusion of divine riches, now began deep in their hearts to cherish envy. Thus one of them persisted with minute inquiries, asking who was the master of this heavenly household and who or what was Psyche’s husband. Psyche, however, scrupulously respected her husband’s orders and did not allow herself to forget them; she improvised a story that he was a handsome young man whose beard had only just begun to grow and that he spent most of his time farming or hunting in the mountains. Then, fearing that if the conversation went on too long some slip would give away her secret thoughts, she loaded them with gold plate and jewellery, immediately summoned Zephyr, and handed them over to him for their return journey.

No sooner said than done. The worthy sisters on their return home were now inflamed by the poison of their growing envy, and began to exchange vociferous complaints. So then the first started: ‘You see the blindness, the cruelty and injustice of Fortune! – content, it would seem, that sisters of the same parents should fare so differently. Here are we, the elder sisters, handed over to foreign husbands as slaves, banished from our home, our own country, to live the life of exiles far from our parents, while she, the youngest, the offspring of a late birth from a worn-out womb, enjoys huge wealth and a god for husband. Why, she doesn’t even know how to make proper use of all these blessings. You saw, sister, all the priceless necklaces, the resplendent stuffs, the sparkling gems, the gold everywhere underfoot. If this husband of hers is as handsome as she says, she is the happiest woman alive. Perhaps, though, as he learns to know her and his love is strengthened, her god-husband will make her a goddess too. Yes, yes, that’s it: that explains her behaviour and her attitude. She’s already looking to heaven and fancying herself a goddess, this woman who has voices for slaves and lords it over the winds themselves. And I, God help me, am fobbed off with a husband older than my father, bald as a pumpkin and puny as a child, who keeps the whole house shut up with bolts and bars.’

Her sister took up the refrain: ‘And I have to put up with a husband bent double with rheumatism and so hardly ever able to give me what a woman wants. I’m always having to massage his twisted, stone-hard fingers, spoiling these delicate hands of mine with stinking compresses and filthy bandages and loathsome plasters – so that it’s not a dutiful wife I look like but an overworked sick-nurse. You must decide for yourself, sister, how patiently – or rather slavishly, for I shall say frankly what I think – you can bear this; as for me, I can no longer stand the sight of such good fortune befalling one so unworthy of it. Do you remember the pride, the arrogance, with which she treated us? How her boasting, her shameless showing off, revealed her puffed-up heart? With what bad grace she tossed us a few scraps of her vast wealth and then without more ado, tiring of our company, ordered us to be thrust – blown – whistled away? As I’m a woman, as sure as I stand here, I’ll hurl her down to ruin from her great riches. And if you too, as you have every right to do, have taken offence at her contemptuous treatment of us, let us put our heads together to devise strong measures. Let us not show these presents to our parents or to anybody else, and let us pretend not to know even whether she is alive or dead. It’s enough that we’ve seen what we wish we hadn’t, without spreading this happy news of her to them and to the rest of the world. You aren’t really rich if nobody knows that you are. She is going to find out that she has elder sisters, not servants. Now let us return to our husbands and go back to our homes – poor but decent – and then when we’ve thought things over seriously let us equip ourselves with an even firmer resolve to punish her insolence.’

The two evil women thought well of this wicked plan, and having hidden all their precious gifts, they tore their hair and clawed their cheeks (no more than they deserved), renewing their pretence of mourning. In this way they inflamed their parents’ grief all over again; and then, taking a hasty leave of them, they made off to their homes swollen with mad rage, to devise their wicked – their murderous – plot against their innocent sister. Meanwhile Psyche’s mysterious husband once more warned her as they talked together that night: ‘Don’t you see the danger that threatens you? Fortune is now engaging your outposts, and if you do not stand very firmly on your guard she will soon be grappling with you hand to hand. These treacherous she-wolves are doing their best to lay a horrible trap for you; their one aim is to persuade you to try to know my face – but if you do see it, as I have constantly told you, you will not see it. So then if those vile witches come, as I know they will, armed with their deadly designs, you must not even talk to them; but if because of your natural lack of guile and tenderness of heart you are unequal to that, at least you must refuse to listen to or answer any questions about your husband. For before long we are going to increase our family; your womb, until now a child’s, is carrying a child for us in its turn – who, if you hide our secret in silence, will be divine, but if you divulge it, he will be mortal.’ Hearing this, Psyche, blooming with happiness, clapped her hands at the consoling thought of a divine child, exulting in the glory of this pledge that was to come and rejoicing in the dignity of being called a mother. Anxiously she counted the growing tale of days and months as they passed, and as she learned to bear her unfamiliar burden she marvelled that from a moment’s pain there should come so fair an increase of her rich womb.

But now those plagues, foulest Furies, breathing viperine poison and pressing on in their devilish haste, had started their voyage; and once more her transitory husband warned Psyche: ‘The day of reckoning and the last chance are here. Your own sex, your own flesh and blood, are the enemy, arrayed in arms against you; they have marched out and drawn up their line, and sounded the trumpet-call; with drawn sword your abominable sisters are making for your throat. What disasters press upon us, sweetest Psyche! Have pity on yourself and on us both; remember your duty and control yourself, save your home, your husband, and this little son of ours from the catastrophe that threatens us. You cannot call those wicked women sisters any longer; in their murderous hatred they have spurned the ties of blood. Do not look at them, do not listen to them, when like the Sirens aloft on their crag they make the rocks ring with their deadly voices.’

As she replied, Psyche’s voice was muffled by sobs and tears: ‘More than once, I know, you have put my loyalty and discretion to the proof, but none the less now you shall approve my strength of mind. Only once more order our Zephyr to do his duty, and instead of your own sacred face that is denied me let me at least behold my sisters. By those fragrant locks that hang so abundantly, by those soft smooth cheeks so like mine, by that breast warm with hidden heat, as I hope to see your face at least in this little one: be swayed by the dutiful prayers of an anxious suppliant, allow me to enjoy my sisters’ embrace, and restore and delight the soul of your devoted Psyche. As to your face, I ask nothing more; even the darkness of night does not blind me; I have you as my light.’ Enchanted by her words and her soft embrace, her husband dried her tears with his hair, promised to do as she asked, and then left at once just as day was dawning.

The two sisters, sworn accomplices, without even visiting their parents, disembarked and made their way at breakneck speed straight to the well-known rock, where, without waiting for their conveying wind to appear, they launched themselves with reckless daring into the void. However, Zephyr, heeding though reluctantly his royal master’s commands, received them in the embrace of his gentle breeze and brought them to the ground. Without losing a second they immediately marched into the palace in close order, and embracing their victim these women who belied the name of sister, hiding their rich store of treachery under smiling faces, began to fawn on her: ‘Psyche, not little Psyche any longer, so you too are a mother! Only fancy what a blessing for us you are carrying in your little pocket! Think of the joy and gladness for our whole house! Imagine what pleasure we shall take in raising this marvellous child! If he is, as he ought to be, as fair as his parents, it will be a real Cupid that will be born.’

With such pretended affection did they little by little make their way into their sister’s heart.

Then and there she sat them down to recover from the fatigues of their journey, provided warm baths for their refreshment, and then at table entertained them splendidly with all those wonderful rich eatables and savoury delicacies of hers. She gave an order, and the lyre played; another, and there was pipe- music; another, and the choir sang. All these invisible musicians soothed with their sweet strains the hearts of the listeners. Not that the malice of the wicked sisters was softened or quieted even by the honeyed sweetness of the music; directing their conversation towards the trap their guile had staked out they craftily began to ask Psyche about her husband, his family, his class, his occupation. She, silly girl that she was, forgetting what she had said before, concocted a new story and told them that her husband was a prosperous merchant from the neighbouring province, a middle-aged man with a few white hairs here and there. However, she did not dwell on this for more than a moment or two, but again returned them to their aerial transport loaded with rich gifts.

No sooner were they on their way back, carried aloft by Zephyr’s calm breath, than they began to hold forth to each other: ‘Well, sister, what is one to say about that silly baggage’s fantastic lies? Last time it was a youth with a fluffy beard, now it’s a middle-aged man with white hair. Who is this who in a matter of days has been suddenly transformed into an old man? Take it from me, sister, either the little bitch is telling a pack of lies or she doesn’t know what her husband looks like. Whichever it is, she must be relieved of those riches of hers without more ado. If she doesn’t know his shape, obviously it is a god she has married and it’s a god her pregnancy will bring us. All I can say is, if she’s called – God forbid – the mother of a divine child, I’ll hang myself and be done with it. Meanwhile then let us go back to our parents, and we’ll patch together the most colourable fabrication we can to support what we’ve agreed on.’

On fire with this idea they merely greeted their parents in passing; and having spent a disturbed and wakeful night, in the morning they flew to the rock. Under the protection as usual of the wind they swooped down in a fury, and rubbing their eyelids to bring on the tears they craftily accosted the girl: ‘There you sit, happy and blessed in your very ignorance of your misfortune and careless of your danger, while we can’t sleep for watching over your welfare, and are suffering acute torments in your distress. For we know for a fact, and you know we share all your troubles and misfortunes, so we cannot hide it from you, that it is an immense serpent, writhing its knotted coils, its bloody jaws dripping deadly poison, its maw gaping deep, if only you knew it, that sleeps with you each night. Remember now the Pythian oracle, which gave out that you were fated to wed a wild beast. Many peasants and hunters of the region and many of your neighbours have seen him coming back from feeding and bathing in the waters of the nearby river. They all say that it won’t be for long that he will go on fattening you so obligingly, but that as soon as the fullness of your womb brings your pregnancy to maturity and you are that much more rich and enjoyable a prize, he will eat you up. Well, there it is; it’s you who must decide whether to take the advice of your sisters who are worried for your life, and escape death by coming to live in safety with us, or be entombed in the entrails of a savage monster. However, if a country life and musical solitude, and the loathsome and dangerous intimacy of clandestine love, and the embraces of a venomous serpent, are what appeals to you, at all events your loving sisters will have done their duty.’

Then poor Psyche, simple and childish creature that she was, was seized by fear at these grim words. Beside herself, she totally forgot all her husband’s warnings and her own promises, and hurled herself headlong into an abyss of calamity. Trembling, her face bloodless and ghastly, she scarcely managed after several attempts to whisper from half-opened lips: ‘Dearest sisters, you never fail in your loving duty, as is right and proper, and I do not believe that those who have told you these things are lying. For I have never seen my husband’s face and I have no idea where he comes from; only at night, obeying his voice, do I submit to this husband of unknown condition – one who altogether shuns the light; and when you say that he must be some sort of wild beast, I can only agree with you. For he constantly terrifies me with warnings not to try to look at him, and threatens me with a fearful fate if I am curious about his appearance. So if you can offer some way of escape to your sister in her peril, support her now: for if you desert me at this point, all the benefits of your earlier concern will be lost.’

The gates were now thrown open, and these wicked women stormed Psyche’s defenceless heart; they ceased sapping and mining, drew the swords of their treachery, and attacked the panic-stricken thoughts of the simple-minded girl. First one began: ‘Since the ties of blood forbid us to consider danger when your safety is at stake, let us show you the only way that can save you, one that we have long planned. Take a very sharp blade and give it an additional edge by stropping it gently on your palm, then surreptitiously hide it on your side of the bed; get ready a lamp and fill it with oil, then when it is burning brightly put it under cover of ajar of some kind, keeping all these preparations absolutely secret; and then, when he comes, leaving his furrowed trail behind him, and mounts the bed as usual, as he lies outstretched and, enfolded in his first heavy sleep, begins to breathe deeply, slip out of bed and with bare feet taking tiny steps one by one on tiptoe, free the lamp from its prison of blind darkness; and consulting the light as to the best moment for your glorious deed, with that two-edged weapon, boldly, first raising high your right hand, with powerful stroke, there where the deadly serpent’s head and neck are joined – cut them apart. Our help will not be wanting; the instant you have secured yourself by his death, we shall be anxiously awaiting the moment to fly to you; then we will take all these riches back along with you and make a desirable marriage for you, human being to human being.’

Their sister had been on fire; these words kindled her heart to a fierce flame. They immediately left her, fearing acutely to be found anywhere near such a crime. Carried back as usual on the wings of the wind and deposited on the rock, they at once made themselves scarce, embarked, and sailed away. But Psyche, alone now except for the savage Furies who harried her, was tossed to and fro in her anguish like the waves of the sea. Though she had taken her decision and made up her mind, now that she came to put her hand to the deed she began to waver, unsure of her resolve, torn by the conflicting emotions of her terrible situation. Now she was eager, now she would put it off; now she dared, now she drew back; now she was in despair, now in a rage; and, in a word, in one and the same body she loathed the monster and loved the husband. However, when evening ushered in the night, she hurried to prepare for her dreadful deed. Night came, and with, it her husband, who, having first engaged on the field of love, fell into a deep sleep.

Then Psyche, though naturally weak in body, rallied her strength with cruel Fate reinforcing it, produced the lamp, seized the blade, and took on a man’s courage. But as soon as the light was brought out and the secret of their bed became plain, what she saw was of all wild beasts the most soft and sweet of monsters, none other than Cupid himself, the fair god fairly lying asleep. At the sight the flame of the lamp was gladdened and flared up, and her blade began to repent its blasphemous edge. Psyche, unnerved by the wonderful vision, was no longer mistress of herself:

feeble, pale, trembling and powerless, she crouched down and tried to hide the steel by burying it in her own bosom; and she would certainly have done it, had not the steel in fear of such a crime slipped and flown out of her rash hands. Now, overcome and utterly lost as she was, yet as she gazed and gazed on the beauty of the god’s face, her spirits returned. She saw a rich head of golden hair dripping with ambrosia, a milk-white neck, and rosy cheeks over which there strayed coils of hair becomingly arranged, some hanging in front, some behind, shining with such extreme brilliance that the lamplight itself flickered uncertainly. On the shoulders of the flying god there sparkled wings, dewy-white with glistening sheen, and though they were at rest the soft delicate down at their edges quivered and rippled in incessant play. The rest of the god’s body was smooth and shining and such as Venus need not be ashamed of in her son. At the foot of the bed lay a bow, a quiver, and arrows, the gracious weapons of the great god.

Curious as ever, Psyche could not restrain herself from examining and handling and admiring her husband’s weapons. She took one of the arrows out of the quiver and tried the point by pricking her thumb; but as her hands were still trembling she used too much force, so that the point went right in and tiny drops of blood bedewed her skin. Thus without realizing it Psyche through her own act fell in love with Love. Then ever more on fire with desire for Desire she hung over him gazing in distraction and devoured him with quick sensuous kisses, fearing all the time that he might wake up. Carried away by joy and sick with love, her heart was in turmoil; but meanwhile that wretched lamp, either through base treachery, or in jealous malice, or because it longed itself to touch such beauty and as it were to kiss it, disgorged from its spout a drop of hot oil on to the right shoulder of the god. What! Rash and reckless lamp, lowly instrument of love, to burn the lord of universal fire himself, when it must have been a lover who first invented the lamp so that he could enjoy his desires for even longer at night! The god, thus burned, leapt up, and seeing his confidence betrayed and sullied, flew off from the loving embrace of his unhappy wife without uttering a word.

But as he rose Psyche just managed to seize his right leg with both hands, a pitiful passenger in his lofty flight; trailing attendance through the clouds she clung on underneath, but finally in her exhaustion fell to the ground. Her divine lover did not abandon her as she lay there, but alighting in a nearby cypress he spoke to her from its lofty top with deep emotion: ‘Simple-minded Psyche, forgetting the instructions of my mother Venus, who ordered that you should be bound by desire for the lowest of wretches and enslaved to a degrading marriage, I myself flew to you instead as your lover. But this I did, I know, recklessly; I, the famous archer, wounded myself with my own weapons and made you my wife – so that, it seems, you might look on me as a monster and cut off this head which carries these eyes that love you. This is what I again and again advised you to be always on your guard against; this is what I repeatedly warned of in my care for you. But those worthy counsellors of yours shall speedily pay the price of their pernicious teaching; your punishment shall merely be that I shall leave you.’ And with these last words he launched himself aloft on his wings.

Psyche, as she lay and watched her husband’s flight for as long as she could see him, grieved and lamented bitterly. But when with sweeping wings he had soared away and she had altogether lost sight of him in the distance, she threw herself headlong off the bank of a nearby stream. But the gentle river, in respect it would seem for the god who is wont to scorch even water, and fearing for himself, immediately bore her up unharmed on his current and landed her on his grassy bank. It happened that the country god Pan was sitting there with the mountain nymph Echo in his arms, teaching her to repeat all kinds of song. By the bank his kids browsed and frolicked at large, cropping the greenery of the river. The goat-god, aware no matter how of her plight, called the lovesick and suffering Psyche to him kindly and caressed her with soothing words: ‘Pretty child, I may be a rustic and a herdsman, but age and experience have taught me a great deal. If I guess aright – and this indeed is what learned men style divination – from these tottering and uncertain steps of yours, and from your deathly pallor, and from your continual sighing, and from your swimming eyes, you are desperately in love. Listen to me then, and do not try to destroy yourself again by jumping off heights or by any other kind of unnatural death. Stop weeping and lay aside your grief; rather adore in prayer Cupid, greatest of gods, and strive to earn his favour, young wanton and pleasure-loving that he is, through tender service.

These were the words of the herdsman-god. Psyche made no reply, but having worshipped his saving power went on her way. But when she had wandered far and wide with toilsome steps, as day waned she came without realizing it by a certain path to the city where the husband of one of her sisters was king. On discovering this, Psyche had herself announced to her sister. She was ushered in, and after they had exchanged greetings and embraces she was asked why she had come. Psyche replied: ‘You remember the advice you both gave me, how you persuaded me to kill with two-edged blade the monster who slept with me under the false name of husband, before he swallowed me up, poor wretch, in his greedy maw. I agreed; but as soon as with the conniving light I set eyes on his face, I saw a wonderful, a divine spectacle, the son of Venus himself, I mean Cupid, deeply and peacefully asleep. But as I was thrilling to the glorious sight, overwhelmed with pleasure but in anguish because I was powerless to enjoy it, by the unhappiest of chances the lamp spilt a drop of boiling oil on to his shoulder. Aroused instandy from sleep by the pain, and seeing me armed with steel and flame, “For this foul crime,” he said, “leave my bed this instant and take your chattels with you. I shall wed your sister” – and he named you – “in due form.” And immediately he ordered Zephyr to waft me outside the boundaries of his palace.’

Before Psyche had finished speaking, her sister, stung by frantic lust and malignant jealousy, concocted on the spot a story to deceive her husband, to the effect that she had had news of her parents’ death, and immediately took ship and hurried to the well-known rock. There, though the wind was blowing from quite a different quarter, yet besotted with blind hope she cried: ‘Receive me, Cupid, a wife worthy of you, and you, Zephyr, bear up your mistress’, and with a mighty leap threw herself over. But not even in death did she reach the place she sought: for as she fell from one rocky crag to another she was torn limb from limb, and she died providing a banquet of her mangled flesh, as she so richly deserved, for the birds of prey and wild beasts. The second vengeance soon followed. For Psyche again in her wanderings arrived at another city, where her second sister likewise lived. She too was no less readily taken in by her sister’s ruse, and eager to supplant her in an unhallowed marriage she hurried off to the rock and fell to a similar death.

Meanwhile, as Psyche was scouring the earth, bent on her search for Cupid, he lay groaning with the pain of the burn in his mother’s chamber. At this point a tern, that pure white bird which skims over the sea-waves in its flight, plunged down swiftly to the very bottom of the sea. There sure enough was Venus bathing and swimming; and perching by her the bird told her that her son had been burned and lay suffering from the sharp pain of his wound and in peril of his life. Now throughout the whole world the good name of all Venus’ family was besmirched by all kinds of slanderous reports. People were saying: ‘Fie has withdrawn to whoring in the mountains, she to swimming in the sea; and so there is no pleasure anywhere, no grace, no charm, everything is rough, savage, uncouth. There are no more marriages, no more mutual friendships, no children’s love, nothing but endless squalor and repellent, distasteful, and sordid couplings.’ Such were the slanders this garrulous and meddlesome bird whispered in Venus’ ear to damage her son’s honour. Venus was utterly furious and exclaimed: ‘So then, this worthy son of mine has a mistress? You’re the only servant I have that I can trust: out with it, the name of this creature who has debauched a simple childish boy – is it one of the tribe of the Nymphs, or one of the number of the Hours, or one of the choir of the Muses, or one of my attendant Graces?’ The voluble bird answered promptly: ‘I do not know, my lady; but I think it’s a girl called Psyche, if I remember rightly, whom he loves to distraction.’ Venus, outraged, cried out loud: ‘Psyche is it, my rival in beauty, the usurper of my name, whom he loves? Really? I suppose my lord took me for a go-between to introduce him to the girl?’

Proclaiming her wrongs in this way she hurriedly left the sea and went at once to her golden bedchamber, where she found her ailing son as she had been told. Hardly had she passed through the door when she started to shout at him: ‘Fine goings-on, these, a credit to our family and your character for virtue! First you ride roughshod over your mother’s – no, your sovereign’s – orders, by nottormenting my enemy with a base amour; then you, a mere child, actually receive her in your vicious adolescent embraces, so that I have to have my enemy as my daughter-in-law. I suppose you think, you odious good-for-nothing lecher, that you’re the only one fit to breed and that I’m now too old to conceive? Let me tell you, I’ll bear another son much better than you – better still, to make you feel the insult more, I’ll adopt one of my household slaves and give him those wings and torch, and bow and arrows too, and all that gear of mine, which I didn’t give you to be used like this – for there was no allowance for this outfit from your father’s estate. But you were badly brought up from a baby, quarrelsome, always insolently hitting your elders. Your own mother, me I say, you expose and abuse every day, battering me all the time, despising me, I suppose, as an unprotected female – and you’re not afraid of that mighty warrior your stepfather. Naturally enough, seeing that you’re in the habit of providing him with girls, to torment me with his infidelities. But I’ll see to it that you’re sorry for these games and find out that this marriage of yours has a sour and bitter taste. But now, being mocked like this, what am I to do? Where am I to turn? How am I to control this reptile? Shall I seek assistance from Sobriety, when I have so often offended her through this creature’s wantonness? No, I won’t, I won’t, have any dealings with such an uncouth and unkempt female. But then the consolation of revenge isn’t to be scorned, whatever its source. Her aid and hers alone is what I must enlist, to administer severe correction to this layabout, to undo his quiver, blunt his arrows, unstring his bow, put out his torch, and coerce him with some sharper corporal medicine. I’ll believe that his insolence to me has been fully atoned for only when she has shaved off the locks to which I have so often imparted a golden sheen by my caressing hands, and cut off the wings which I have groomed with nectar from my own breasts.’

With these words she rushed violently out in a fury of truly Venerean anger. The first persons she met were Ceres and Juno, who seeing her face all swollen with rage, asked her why she was frowning so grimly and spoiling the shining beauty of her eyes. To which she answered: ‘You’ve come just at the right moment to satisfy the desire with which my heart is burning. Please, I beg you, do your utmost to find that runaway fly-by-night Psyche for me, for you two must be well aware of the scandal of my house and of what my son – not that he deserves the name – has been doing.’ They, knowing perfectly well what had happened, tried to soothe Venus’ violent rage: ‘Madam, what has your son done that’s so dreadful that you are determined to thwart his pleasures and even want to destroy the one he loves? Is it really a crime, for heaven’s sake, to have been so ready to give the glad eye to a nice girl? Don’t you realize that he is a young man? You must have forgotten how old he is now. Perhaps because he carries his years so prettily, he always seems a boy to you? Are you, a mother and a woman of sense, to be forever inquiring into all his diversions, checking his little escapades, and showing up his love-affairs? Aren’t you condemning in your fair son your own arts and pleasures? Gods and men alike will find it intolerable that you spread desire broadcast throughout the world, while you impose a bitter constraint on love in your own family and deny it admission to your own public academy of gallantry.’ In this way, fearful of his arrows, did they flatter Cupid in his absence with their ingratiating defense of his cause. But Venus took it ill that her grievances should be treated so lightly, and cutting them short made off quickly in the other direction, back towards the sea.

Psyche meanwhile was wandering far and wide, searching day and night for her husband, and the sicker she was at heart, the more eager she was, if she could not mollify him by wifely endearments, at least to appease his anger by beseeching him as a slave. Seeing a temple on the top of a steep hill, ‘Perhaps,’ said she, ‘my lord lives there’; at once she made for it, her pace, which had flagged in her unbroken fatigues, now quickened by hope and desire. Having stoutly climbed the lofty slopes she approached the shrine. There she saw ears of corn, some heaped up, some woven into garlands, together with ears of barley. There were also sickles and every kind of harvesting gear, all lying anyhow in neglect and confusion and looking, as happens in summer, as if they had just been dropped from the workers’ hands. All these things Psyche carefully sorted and separated, each in its proper place, and arranged as they ought to be, thinking evidently that she should not neglect the shrines or worship of any god, but should implore the goodwill and pity of them all.

She was diligently and busily engaged on this task when bountiful Ceres found her, and with a deep sigh said: ‘So, poor Psyche! There is Venus in her rage dogging your footsteps with painstaking inquiries through the whole world, singling you out for dire punishment, and demanding revenge with the whole power of her godhead; and here are you taking charge of my shrine and thinking of anything rather than your own safety.’ Psyche fell down before her, and bedewing her feet with a flood of tears, her hair trailing on the ground, she implored the goddess’s favour in an elaborate prayer: ‘I beseech you, by this your fructifying hand, by the fertile rites of harvest, by the inviolate secrets of the caskets, by the winged chariot of your dragon-servants, by the furrows of the Sicilian fields, by the car that snatches and the earth that catches, by your daughter Proserpine’s descent to her lightless wedding and her return to bright discovery, and all else that the sanctuary of Attic Eleusis conceals in silence: support the pitiful spirit of your suppliant Psyche. Allow me to hide for only a very few days among these heaps of corn, until the great goddess’s fierce anger is soothed by the passing of time or at least until my strength is recruited from the fatigues of long suffering by an interval of rest.’ Ceres answered: ‘Your tearful prayers indeed move me and make me wish to help you; but I cannot offend my kinswoman, who is a dear friend of long standing and a thoroughly good sort. So you must leave this place at once, and think yourself lucky that you are not my prisoner.’

Disappointed and rebuffed, the prey of a double sadness, Psyche was retracing her steps, when in the half-light of a wooded valley which lay before her she saw a temple built with cunning art. Not wishing to neglect any prospect, however doubtful, of better hopes, but willing to implore the favour of any and every god, she drew near to the holy entrance. There she saw precious offerings and cloths lettered in gold affixed to trees and to the doorposts, attesting the name of the goddess to whom they were dedicated in gratitude for her aid. Then, kneeling and embracing the yet warm altar, she wiped away her tears and prayed: ‘Sister and consort of great Jove, whether you are at home in your ancient shrine on Samos, which alone glories in having seen your birth, heard your first cries, and nourished your infancy; or whether you dwell in your rich abode in lofty Carthage, which worships you as a virgin riding the heavens on a lion; or whether by the bilks of Inachus, who hails you now as bride of the Thunderer and queen of goddesses, you rule over the famous citadel of Argos; you who are worshipped by the whole East as Zygia and whom all the West calls Lucina: be in my desperate need Juno who Saves, and save me, worn out by the great sufferings I have gone through, from the danger that hangs over me. Have I not been told that it is you who are wont to come uncalled to the aid of pregnant women when they are in peril?’ As she supplicated thus, Juno immediately manifested herself in all the awesome dignity of her godhead, and replied: ‘Believe me, I should like to grant your prayers. But I cannot for shame oppose myself to the wishes of my daughter-in-law Venus, whom I have always loved as my own child. Then too I am prevented by the laws which forbid me to receive another person’s runaway slaves against their master’s wishes.’

Psyche was completely disheartened by this second shipwreck that Fortune had contrived for her, and with no prospect of finding her winged husband she gave up all hope of salvation. So she took counsel with herself: ‘Now what other aid can I try, or bring to bear on my distresses, seeing that not even the goddesses’ influence can help me, though they would like to? Trapped in this net, where can I turn? What shelter is there, what dark hiding-place, where I can escape the unavoidable eyes of great Venus? No, this is the end: I must summon up a man’s spirit, boldly renounce my empty remnants of hope, give myself up to my mistress of my own free will, and appease her violence by submission, late though it will be. And perhaps he whom I have sought so long may be found there in his mother’s house.’ So, prepared for submission with all its dangers, indeed for certain destruction, she thought over how she should begin the prayer she would utter.

Venus, however, had given up earthbound expedients in her search, and set off for heaven. She ordered to be prepared the car that Vulcan the goldsmith god had lovingly perfected with cunning workmanship and given her as a betrothal present — a work of art that made its impression by what his refining tools had pared away, valuable through the very loss of gold. Of the many doves quartered round their mistress’s chamber there came forth four all white; stepping joyfully and twisting their coloured necks around they submitted to the jewelled yoke, then with their mistress on board they gaily took the air. The car was attended by a retinue of sportive sparrows frolicking around with their noisy chatter, and of other sweet-voiced birds who, singing in honey-toned strains, harmoniously proclaimed the advent of the goddess. The clouds parted, heaven opened for his daughter, and highest Aether joyfully welcomed the goddess; great Venus’ tuneful entourage has no fear of ambushes from eagles or rapacious hawks.

She immediately headed for Jove’s royal citadel and haughtily demanded an essential loan — the services of Mercury, the loud- voiced god. Jove nodded his dark brow, and she in triumph left heaven then and there with Mercury, to whom she earnestly spoke: ‘Arcadian brother, you know well that your sister Venus has never done anything without Mercury’s assistance, and you must be aware too of how long it is that I have been trying in vain to find my skulking handmaid. All we can do now is for you as herald to make public proclamation of a reward for her discovery. Do my bidding then at once, and describe clearly the signs by which she can be recognized, so that if anybody is charged with illegally concealing her, he cannot defend himself with a plea of ignorance’; and with these words she gave him a paper with Psyche’s name and the other details. That done, she returned straight home.

Mercury duly obeyed her. Passing far and wide among the peoples he carried out his assignment and made proclamation as ordered: ‘If any man can recapture or show the hiding-place of a king’s runaway daughter, the slave of Venus, by name Psyche, let him report to Mercury the crier behind the South turning-point of the Circus, and by way of reward for his information he shall receive from Venus herself seven sweet kisses and an extra one deeply honeyed with the sweetness of her thrusting tongue.’ This proclamation of Mercury’s and the desire for such a reward aroused eager competition all over the world. Its effect on Psyche was to put an end to all her hesitation. As she neared her mistress’s door she was met by one of Venus’ household named Habit, who on seeing her cried out at the top of her voice: ‘At last, you worthless slut, you’ve begun to realize you have a mistress? Or will you with your usual impudence pretend you don’t know how much trouble we’ve had looking for you? A good thing you’ve fallen into my hands; you’re held in the grip of Orcus, and you can be sure you won’t have to wait long for the punishment of your disobedience.’ So saying, she laid violent hands on Psyche’s hair and dragged her inside unresisting. As soon as Venus saw her brought in and presented to her, she laughed shrilly, as people do in a rage; and shaking her head and scratching her right ear, ‘So,’ she said, ‘you have finally condescended to pay your respects to your mother-in-law? Or is it your husband you’ve come to visit, who lies under threat of death from the wound you’ve dealt him? But don’t worry, I will receive you as a good daughter-in-law deserves.’ Then, ‘Where are my handmaids Care and Sorrow?’ she asked. They were called in, and Psyche was handed over to them to be tormented. In obedience to their mistress’s orders they whipped the wretched girl and afflicted her with every other kind of torture, and then brought her back to face the goddess. Venus, laughing again, exclaimed: ‘Look at her, trying to arouse my pity through the allurement of her swollen belly, whose glorious offspring is to make me, thank you very much, a happy grandmother. What joy, to be called grandmother in the flower of my age and to hear the son of a vile slave styled Venus’ grandson! But why am I talking about sons? This isn’t a marriage between equals, and what’s more it took place in the country, without witnesses, and without his father’s consent, and can’t be held to be legitimate. So it will be born a bastard, if indeed I allow you to bear it at all.’

With these words, she flew at Psyche, ripped her clothes to shreds, tore her hair, boxed her ears, and beat her unmercifully. Then she took wheat and barley and millet and poppy-seed and chick-peas and lentils and beans, mixed them thoroughly all together in a single heap, and told Psyche: ‘Now, since it seems to me that, ugly slave that you are, you can earn the favours of your lovers only by diligent drudgery, I’m now going to put your merit to the test myself. Sort out this random heap of seeds, and let me see the work completed this evening, with each kind of grain properly arranged and separated.’ And leaving her with the enormous heap of grains, Venus went off to a wedding-dinner.

Psyche did not attempt to touch the disordered and unmanageable mass, but stood in silent stupefaction, stunned by this monstrous command. Then there appeared an ant, one of those miniature farmers; grasping the size of the problem, pitying the plight of the great god’s bedfellow and execrating her mother-in-law’s cruelty, it rushed round eagerly to summon and convene the whole assembly of the local ants. ‘Have pity,’ it cried, ‘nimble children of Earth the all-mother, have pity and run with all speed to the aid of the sweet girl-wife of Love in her peril.’ In wave after wave the six-footed tribes poured in to the rescue, and working at top speed they sorted out the whole heap grain by grain, separated and distributed the seed by kinds, and vanished swiftly from view.

At nightfall Venus returned from the banquet flushed with wine, fragrant with perfume, and garlanded all over with brilliant roses. When she saw the wonderful exactness with which the task had been performed, ‘Worthless wretch!’ she exclaimed, ‘this is not your doing or the work of your hands, but his whose fancy you have taken — so much the worse indeed for you, and for him’; and throwing Psyche a crust of coarse bread she took herself to bed. Meanwhile Cupid was under strict guard, in solitary confinement in one room at the back of the palace, partly to stop him from aggravating his wound through his impetuous passion, partly to stop him from seeing his beloved. So then the two lovers, though under the same roof, were kept apart and endured a melancholy night. As soon as Dawn took horse, Venus called Psyche and said: ‘You see that wood which stretches along the banks of the river which washes it in passing, and the bushes at its edge which look down on the nearby spring? Sheep that shine with fleece of real gold wander and graze there unguarded. Of that precious wool see that you get a tuft by hook or by crook and bring it to me directly.’

Psyche set out willingly, not because she expected to fulfil her task, but meaning to find a respite from her sufferings by throwing herself from a rock into the river. But then from the river a green reed, source of sweet music, divinely inspired by the gentle whisper of the soft breeze, thus prophesied: ‘Psyche, tried by much suffering, do not pollute my holy waters by your pitiable death. This is not the moment to approach these fearsome sheep, while they are taking in heat from the blazing sun and are maddened by fierce rage; their horns are sharp and their foreheads hard as stone, and they often attack and kill men with their poisonous bites. Rather, until the midday heat of the sun abates and the flock is quietened by the soothing breeze off the river, you can hide under that tall plane which drinks the current together with me. Then, when their rage is calmed and their attention is relaxed, shake the branches of the nearby trees, and you will find the golden wool which sticks everywhere in their entwined stems.’

So this open-hearted reed in its humanity showed the unfortunate Psyche the way to safety.

She paid due heed to its salutary advice and acted accordingly: she did everything she was told and had no trouble in helping herself to a heaped-up armful of the golden softness to bring back to Venus. Not that, from her mistress at least, the successful outcome of her second trial earned her any approval. Venus bent her brows and with an acid smile said: ‘I am not deceived: this exploit too is that lecher’s. Now, however, I shall really exert myself to find out whether you have a truly stout heart and a good head on your shoulders. You see the top of the steep mountain that looms over that lofty crag, from which there flows down the dark waters of a black spring, to be received in a basin of the neighbouring valley, and then to water the marshes of Styx and feed the hoarse streams of Cocytus? There, just where the spring gushes out on the very summit, draw off its ice-cold water and bring it to me instantly in this jar.’ So saying she gave her an urn hollowed out from crystal, adding yet direr threats.

Psyche eagerly quickened her pace towards the mountain-top, expecting to find at least an end of her wretched existence there. But as soon as she approached the summit that Venus had shown her, she saw the deadly difficulty of her enormous task. There stood a rock, huge and lofty, too rough and treacherous to climb; from jaws of stone in its midst it poured out its grim stream, which first gushed from a sloping cleft, then plunged steeply to be hidden in the narrow channel of the path it had carved out for itself, and so to fall by secret ways into the neighbouring valley. To left and right she saw emerging from the rocky hollows fierce serpents with long necks outstretched, their eyes enslaved to unwinking vigilance, forever on the watch and incessantly wakeful. And now the very water defended itself in speech, crying out repeatedly ‘Be off!’ and ‘What are you doing? Look out!’ and ‘What are you about? Take care!’ and ‘Fly!’ and ‘You’ll die!’ Psyche was turned to stone by the sheer impossibility of her task, and though her body was present her senses left her: overwhelmed completely by the weight of dangers she was powerless to cope with, she could not even weep, the last consolation.

But the suffering of this innocent soul did not escape the august eyes of Providence. For the regal bird of almighty Jove, the ravisher eagle, suddenly appeared with outspread wings,

and remembering his former service, how prompted by Cupid he had stolen the Phrygian cupbearer for Jupiter, brought timely aid. In honour of the god’s power, and seeing his wife’s distress, he left Jove’s pathways in the heights, and gliding down before the girl he addressed her: ‘Do you, naive as you are and inexperienced in such things, hope to be able to steal a single drop of this most holy and no less terrible spring, or even touch it? You must have heard that this water of Styx is feared by the gods themselves, even Jupiter, and that the oaths which mortals swear by the power of the gods, the gods s Psyche joyfully received the full urn and took it back at once to Venus. Even then, however, she could not satisfy the wishes of the cruel goddess. Threatening her with yet worse outrages, she addressed Psyche with a deadly smile: ‘I really think you must be some sort of great and profoundly accomplished witch to have carried out so promptly orders like these of mine. But you still have to do me this service, my dear. Take this casket’ (giving it to her) ‘and be off with you to the Underworld and the ghostly abode of Orcus himself. Present it to Proserpine and say: “Venus begs that you send her a little of your beauty, enough at least for one short day. For the supply that she had, she has quite used up and exhausted in looking after her ailing son.” Come back in good time, for I must make myself up from it before going to the theatre of the gods.’

Then indeed Psyche knew that her last hour had come and that all disguise was at an end, and that she was being openly sent to instant destruction. So much was clear, seeing that she was being made to go on her own two feet to Tartarus and the shades. Without delay she made for a certain lofty tower, meaning to throw herself off it: for in that way she thought she could most directly and economically go down to the Underworld. But the tower suddenly broke into speech: ‘Why, poor child, do you want to destroy yourself by a death-leap? Why needlessly give up at this last ordeal? Once your soul is separated from your body, then indeed you will go straight to the pit of Tartarus, but there will be no coming back for you. Listen to me. Not far from here is Sparta, a famous city of Greece. Near to it, hidden in a trackless countryside, you must find Taenarus. There you’ll see the breathing-hole of Dis, and through its gaping portals the forbidden road; once you have passed the threshold and entrusted yourself to it, you will fare by a direct track to the very palace of Orcus. But you must not go through that darkness empty-handed as you are; you must carry in your hands cakes of barley meal soaked in wine and honey, and in your mouth two coins. When you have gone a good way along the infernal road you will meet a lame donkey loaded with wood and with a lame driver; he will ask you to hand him some sticks fallen from the load, but you must say nothing and pass by in silence. Directly after that you will come to the river of death. Its harbourmaster is Charon, who ferries wayfarers to the other bank in his boat of skins only on payment of the fee which he immediately demands. So it seems that avarice lives even among the dead, and a great god like Charon, Dis’s Collector, does nothing for nothing. A poor man on his deathbed must make sure of his journey-money, and if he hasn’t got the coppers to hand, he won’t be allowed to expire. To this unkempt old man you must give one of your coins as his fare, making him take it himself from your mouth.

Then, while you are crossing the sluggish stream, an old dead man swimming over will raise his decaying hands to ask you to haul him aboard; but you must not be swayed by pity, which is forbidden to you. When you are across and have gone a little way, some old women weavers will ask you to lend a hand for a moment to set up their loom; but here too you must not become involved. For all these and many other ruses will be inspired by Venus to make you drop one of your cakes. Don’t think the loss of a paltry barley cake a light thing: if you lose one you will thereby lose the light of the sun. For a huge dog with three enormous heads, a monstrous and fearsome brute, barking thunderously and with empty menace at the dead, whom he can no longer harm, is on perpetual guard before the threshold and dark halls of Proserpine, and watches over the empty house of Dis. Him you can muzzle by letting him have one of your cakes; passing him easily by you will come directly to Proserpine, who will receive you kindly and courteously, urging you to take a soft seat and join her in a rich repast.

But you must sit on the ground and ask for some coarse bread; when you have eaten it you can tell her why you have come, and then taking what you are given you can return. Buy off the fierce dog with your other cake, and then giving the greedy ferryman the coin you have kept you will cross the river and retrace your earlier path until you regain the light of heaven above. But this prohibition above all I bid you observe: do not open or look into the box that you bear or pry at all into its hidden store of divine beauty.’ So this far-sighted tower accomplished its prophetic task. Psyche without delay made for Taenarus, where she duly equipped herself with coins and cakes and made the descent to the Underworld. Passing in silence the lame donkey-driver, paying her fare to the ferryman, ignoring the plea of the dead swimmer, rejecting the crafty entreaties of the weavers, and appeasing the fearsome rage of the dog with her cake, she arrived at Proserpine’s palace. She declined her hostess’s offer of a soft seat and rich food, and sitting on the ground before her feet, content with a piece of coarse bread,

she reported Venus’ commission. The box was immediately taken away to be filled and closed up in private, and given back to Psyche. By the device of the second cake she muzzled the dog’s barking, and giving the ferryman her second coin she returned from the Underworld much more briskly than she had come. Having regained and worshipped the bright light of day, though in a hurry to complete her mission, she madly succumbed to her reckless curiosity. ‘What a fool I am,’ said she, ‘to be carrying divine beauty and not to help myself even to a tiny bit of it, so as perhaps to please my beautiful lover.’ So saying she opened the box. But she found nothing whatever in it, no beauty, but only an infernal sleep, a sleep truly Stygian, which when the lid was taken off and it was let out at once took possession of her and diffused itself in a black cloud of oblivion throughout her whole body, so that overcome by it she collapsed on the spot where she stood in the pathway, and lay motionless, a mere sleeping corpse.

But Cupid’s wound had now healed and, his strength returned, he could no longer bear to be parted for so long from Psyche. He escaped from the high window of the room in which he was confined; and, with his wings restored by his long rest, he flew off at great speed to the side of his Psyche. Carefully wiping off the sleep and replacing it where it had been in the box, he roused her with a harmless prick from one of his arrows. ‘There, poor wretch,’ he said, ‘you see how yet again curiosity has been your undoing. But meanwhile you must complete the mission assigned you by my mother with all diligence; the rest I will see to.’ So saying, her lover nimbly took flight, while Psyche quickly took back Proserpine’s gift to Venus.

Meanwhile Cupid, eaten up with love, looking ill, and dreading his mother’s new-found austerity, became himself again. On swift wings he made his way to the very summit of heaven and pleaded his cause as a suppliant with great Jupiter. Jupiter took Cupid’s face in his hand, pulled it to his own, and kissed him, saying: ‘In spite of the fact, dear boy, that you have never paid me the respect decreed me by the gods in council, but have constantly shot and wounded this breast of mine by which the behaviour of the elements and the movements of the heavenly bodies are regulated, defiling it repeatedly with lustful adventures on earth, compromising my reputation and character by low intrigues in defiance of the laws, the Lex Julia included, and of public morals, changing my majestic features into the base shapes of snakes, of fire, of wild animals, of birds and of farmyard beasts — yet in spite of all, remembering my clemency and that you grew up in my care, I will do what you ask. But you must take care to guard against your rivals; and if there is now any pre-eminently lovely girl on earth, you are bound to pay me back with her for this good turn.’

So saying, he ordered Mercury to summon all the gods immediately to assembly, proclaiming that any absentees from this heavenly meeting would be liable to a fine of ten thousand sesterces. This threat at once filled the divine theatre; and Jupiter, towering on his lofty throne, announced his decision. ‘Conscript deities enrolled in the register of the Muses, you undoubtedly know this young man well, and how I have reared him with my own hands. I have decided that the hot-blooded impulses of his first youth must somehow be bridled; his name has been besmirched long enough in common report by adultery and all kinds of licentious behaviour. We must take away all opportunity for this and confine his youthful excess in the bonds of marriage. He has chosen a girl and had her virginity: let him have and hold her, and embracing Psyche for ever enjoy his beloved.’ Then turning to Venus, ‘Daughter,’ he said, ‘do not be downcast or fear for your great lineage or social standing because of this marriage with a mortal. I shall arrange for it to be not unequal but legitimate and in accordance with the civil law.’ Then he ordered Psyche to be brought by Mercury and introduced into heaven. Handing her a cup of ambrosia, ‘Take this, Psyche,’ he said, ‘and be immortal.

Never shall Cupid quit the tie that binds you, but this marriage shall be perpetual for you both.’

No sooner said than done: a lavish wedding-feast appeared. In the place of honour reclined Psyche’s husband, with his wife in his arms, and likewise Jupiter with his Juno, and then the other gods in order of precedence. Cups of nectar were served to Jove by his own cupbearer, the shepherd lad, and to the others by Liber; Vulcan cooked the dinner; the Seasons made everything colourful with roses and other flowers; the Graces sprinkled perfumes; the Muses discoursed tuneful music. Then Apollo sang to the lyre, and Venus, fitting her steps to the sweet music, danced in all her beauty, having arranged a production in which the Muses were chorus and played the tibia, while a Satyr and a little Pan sang to the shepherd’s pipe.

Thus was Psyche married to Cupid with all proper ceremony, and when her time came there was born to them a daughter, whom we call Pleasure.

Toward a New Definition of Symbolist

Trying to make a clear definition of the Symbolist Movement is a frustrating endeavor. In terms of expressive intent, artists like Gustave Klimt, Ferdinand Knnopff, Arnold Broecklin, can seem very far away from the English Pre-Raphaelite painters like John Waterhouse, Lord Leighton, and Arnold Hacker. How does some one like John E. Millais, arguably a […]